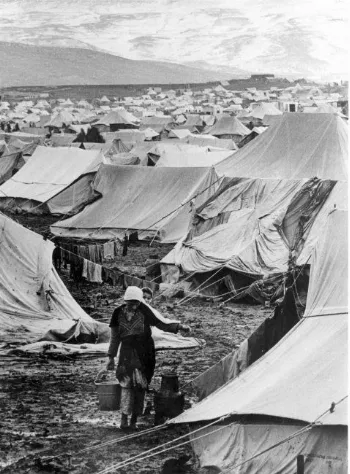

Palestinian refugees in Jordan.

Jordan has been a safe haven for many refugees from various neighboring countries, including Syria and Palestine. Palestinian refugees first came to Jordan during the Arab-Israeli war in 1948. More came later during the 1967 war. About ten thousand Palestinians also came from Syria, complicating their refugee and legal status. This influx has left Jordan supporting the largest number of Palestinian refugees in any single country in the world. Although most Palestinian refugees have been granted full citizenship in Jordan, they are typically still treated as second-class citizens. Many are still living in poverty and do not have adequate access to education and healthcare.

There are ten official Palestine refugee camps throughout Jordan. While Jordan houses almost two million Palestinian refugees, most of them have moved out of the camps to other parts of the country, bringing the number of refugees still living in camps to 370,000, which makes up 18 percent of the country’s total. However, the large number of refugees has perhaps put a strain on Jordan’s finances and resources. The living conditions of the refugees in the camps remain dire. 97 percent of them do not have a social security number, and as such as unable to seek employment in the country. With unemployment rates going to 39 percent, 46 percent of refugees living in the camps are living on a dollar a day, restricted only to low-paid jobs as welders, cleaners and agricultural laborers. The refugees are issued temporary passports, but many are unable to afford the fees to renew it every two years – which increased four times from 50 Jordanian dinar to 200 Jordanian dinar in 2017.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) aims to cater to education for children living in the refugee camps from the ages of six to sixteen. The government provides two more years of education after that until eighteen, but the children are on their own after that. Without social security numbers, they are treated as international students and required to pay tuition fees of 4,200 Jordanian dinar per year for a university education, double the amount citizens pay. While there are a few scholarships available to Palestinians, qualifying for them is a different story. Without the luxury of student loans, many refugee students end up skipping alternate semesters of university to work and earn enough to fund their next semester.

The case of large numbers of refugees in Jordan has had both its advantages and disadvantages. The Jordanian authorities regularly stress that the country has been supporting the highest ratio of refugees to indigenous population in the world, allowing them to receive funds from non-profit organizations and donor countries. Another boost to the Jordanian economy comes in the form of resettlement projects funded by international organizations or United States development agencies.

However, the statistic on just how many refugees Jordan is supporting is hardly acknowledged outside of the Middle East as Palestinians do not fall under the responsibility of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). As such, the real number of Palestinian refugees in Jordan is rarely included in worldwide statistics on refugees. This may be partly due to the fact that most Palestinian refugees in Jordan have been granted citizenship.

Despite the financial aid from donors, Jordan’s economy still continues on a low streak. Its GDP growth has dropped to around 2 percent compared to 6 percent last decade. Inflation rates are at 3.3 percent. To make matters worse, United States President Donald Trump made the decision to hold back $65 million from the $125 million aid to UNRWA on the basis that he felt the Palestinian people were not grateful or respectful to the United States. As a result of reduced financial aid, more Palestinian refugees have been out of jobs and the living conditions and financial situation in the country has not climbed up. With Jordan’s scarce natural resources, the country’s main focus is on tourism and agricultural livelihoods.

The Jordanian leadership has also faced some issues regarding the identity of the country given the large Palestinian population currently residing there. It is said that half to two thirds of the total Jordanian population are made up of Palestinians. As most of the 2 million Palestinian refugees are holding Jordanian citizenships and have integrated into the society, the authorities in Jordan continue to control independent expression of their political claims, disputing the Israeli claim that “Jordan is Palestine” and making Jordan seem less of just a new land for the Palestinians.

The issue of “Palestinian or Jordanian” went through some tension over the 1950s to 1970s. Palestinians were granted citizenship on the conditions of their allegiance to the rulership in Jordan, and that it would protect its own interests before engaging militarily with Israel. While most of the Palestinians accepted the terms and became integrated into Jordan, other educated Palestinians migrated out of Jordan just a few years after they first entered in 1948. When the Palestine Liberation Organization sought to make Jordan its political and military base against Israel in the 1960s, the monarchy in Jordan was threatened and there was regular infighting between the regular army and the organization’s guerillas, the worst of which occurred between 1970 to 1971. The events resulted in a few thousand paramilitary troops and their leaders being expelled from Jordan, some together with their families. Since then, most individuals living in Jordan have been pressured to side with “Jordanian” or “Palestinian”, and are usually required to state their political allegiance even just to secure their jobs and the scarce resources.

Since the past few decades, there has been talk about resettling the Palestinians in Jordan by turning them into permanent citizens. However, Jordanians have been opposed to the idea of turning Jordan into a “Palestinian state”. The issue resurfaced in the past few years with the cutting down of funds from the UNRWA, prompting the fear that Jordan would be required to resettle the Palestinians, especially those who carry temporary passports. It is believed that despite the Palestinians’ longstanding presence in the land, the authorities of Jordan still consider their stay to be temporary and are opposed to permanently resettling the refugees in their lands.

It is not just Jordan that has this mindset, but also the other surrounding Arab countries, including Lebanon and Syria. In fact, the Jordanian authorities made a move to revoke the citizenships of thousands of Palestinians, even those of non-refugees. They explained that they did not wish to grant the Palestinians permanent stay in the lands, so that Israel would not be able to use the permanent citizenship as an excuse to deny the Palestinians a return to their homeland. However, this act was met with opposition from the Palestinians, who claimed that the other Arab countries were opposed to resettlement not because they cared about allowing the Palestinians to return to their homeland but because of other internal and regional considerations.