Space Shuttle Challenger Explosion

On January 28, 1986, a nation anxiously watched as NASA’s second space shuttle to enter service, Challenger, was set to launch into space on its tenth journey. However, just 73 seconds after takeoff, the shuttle exploded, killing all seven crew on board.

Although the disaster is commonly referred to as an explosion and looked like one, it was actually not an explosion in the way we would imagine – there was no detonation. Instead, the spacecraft was torn apart by aerodynamic forces. The fuel tank collapsed, exposing the liquid oxygen and hydrogen within to the atmosphere and creating a huge fireball that looked to be an explosion.

Background

1986 was slated to make history in the line of space travel, with 15 shuttle flights scheduled for the year. The Challenger’s mission, STS-51L, was the first of the lot.

Challenger was NASA’s second space shuttle to enter service. It had embarked on its maiden flight on April 4, 1983. In the time between its launch and 1986, the Challenger had gone on nine missions, with STS-51L being its tenth.

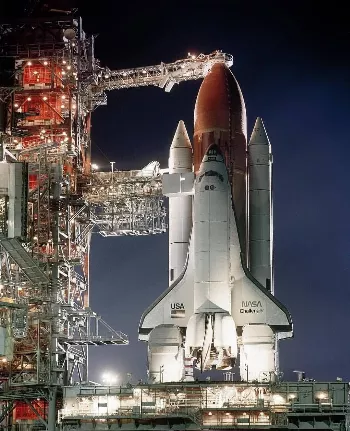

The space shuttle was set to launch from Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Its original launch date was supposed to be on January 22, but the launch was delayed four times due to multiple reasons – a routine scheduling delay, a dust storm at an emergency landing site, inclement weather at the launch site and finally a technical problem with one of the door latch mechanisms.

Although not proven, it has been suggested that NASA had been under pressure to push the launch of the Challenger forward so that it would be in time for the President’s State of the Union address, scheduled for later on January 28. Other political factors have also been alleged, including NASA feeling the competition from other countries who were also exploring shuttle launch. This could also have been attributed to the previous delays for Challenger, partially due to the difficulties NASA faced in getting its previous shuttle Columbia back on the ground.

One of the seven on board the Challenger was Christa McAuliffe, a 37-year-old high school social studies teacher in Concord, New Hampshire. She dreamed of being a passenger in space, so when NASA announced the Teacher in Space program, McAuliffe jumped at the chance and applied for it. She was chosen out of 11,000 applicants for the program as the first ordinary American citizen to travel into space. To prepare for the mission, she had to leave her family and undergo extensive training in Houston, Texas, for a few months.

How Did It Happen?

On the morning of January 28, the temperature was unusually cold. In fact, it had been so cold overnight that large quantities of ice had collected on the launch pad. NASA had never launched a shuttle at such low temperatures before – the coldest temperature any previous shuttles had been launched at was 20 degrees warmer than that of January 28.

Some engineers at the launch site had warned their superiors that some components of the shuttle, particularly the rubber O-ring seals in the solid rocket boosters, were vulnerable to failure in the cold.

The solid rocket boosters were made out of four hull segments, with each segment being filled with powdered aluminum – the fuel – and ammonium perchlorate – the oxidizer. These segments were assembled vertically at the launch site, with rubber O-ring seals installed in between each segment to seal them. However, these O-rings had never been tested in such cold temperatures. On the day of the launch, the O-rings froze and became brittle, resulting in the fuel segments not being fully sealed.

Despite this, Morton Thiokol, the company that built the solid rocket boosters, recommended that NASA proceed with the launch as they expected that the rubber O-rings would be able to take on the cold.

When the Challenger took off at 11:39 AM, one of the O-ring seals broke, allowing exhaust and flames to leak out of the solid rocket booster. These hot gases came into contact with the cold external tank containing liquid oxygen and hydrogen, causing the tank to rupture.

As a result, the space shuttle was torn apart by aerodynamic forces just 73 seconds after liftoff. The crew compartment reached an altitude of 12.3 miles before it crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, killing all crew on board. Meanwhile, the two solid rocket boosters continued flying until they were destroyed by remote control.

Aftermath

The nation was undoubtedly shaken and traumatized by the incident, including the families of Christa McAuliffe and the other six astronauts on board. President Ronald Reagan postponed his State of the Union message to the nation, the first and only time a president has done so in the history of the United States. Instead, he addressed the Challenger incident, ending with a quote from the American pilot John McGee Jr., who had been killed in action during World War II.

Reagan said: “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of Earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.’”

Shortly after, President Reagan appointed a special commission headed by the former secretary of state William Rogers to investigate what happened with the Challenger and to come up with future measures to prevent such a disaster from happening again.

The commission found out that the weakest link in the shuttle was the O-ring seals, which had stiffened due to the cold, allowing flames from the solid rocket boosters to damage the external fuel tank and explode the spacecraft. The investigation also revealed that Morton Thiokol, the company that designed the solid rocket boosters, had ignored prior warnings about the vulnerability of the O-rings in extreme cold. Additionally, NASA managers had been made aware of these potential issues but did not take any action.

Within a day of the disaster, hundreds of pounds of metal were recovered from the wreckage of the Challenger. The crew cabin was found in March 1986, with the remains of the astronauts in it. The investigation was closed later in 1986 and most of the important pieces of the spacecraft retrieved, although most of the shuttle still remained where it crashed in the Atlantic Ocean. However, a decade later, two large pieces of the shuttle washed up at Cocoa Beach, 20 miles south of the Challenger’s launch site at the Kennedy Space Center. These pieces were believed to have been connected, originating from the left wing flap of the Challenger. They were placed in two abandoned missile silos with the rest of the recovered wreckage. The total salvage from the shuttle amounts to around 5,000 pieces and weighs approximately 250,000 pounds.

After the Challenger explosion, NASA temporarily suspended flight programs, refraining from sending any astronauts into space for the next two years. Space flights would resume from 1988 with the successful mission of Discovery, and continue without incident until the 2003 disintegration of Columbia as it re-entered the atmosphere.